When I look up and find myself surrounded by Angus’ work, I go somewhere where I can’t hear the muffled rush of the central London traffic through the closed door. It is the same place I went to when we were on the phone last week, talking about Germany, where the material and inspiration for this exhibition originated. It is also the place I grew up, which is maybe why I feel the works in the show resonate so much. I love London but do get homesick sometimes. Knowing that Angus is in Berlin, now, makes me happy.

We have known each other for some years now. We met when he started working at a gallery in London, immediately getting along talking art (his and others’), books (science fiction), and the UK (still new to me). I was an intern at the time and just visiting, but would later move to London permanently and we became colleagues and finally friends.

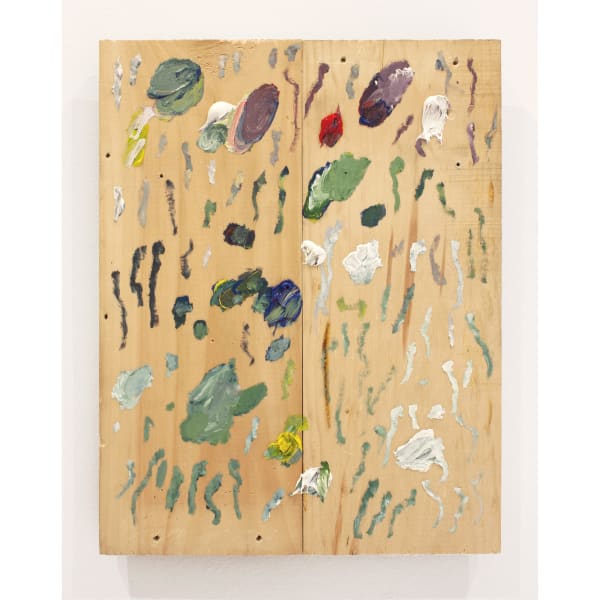

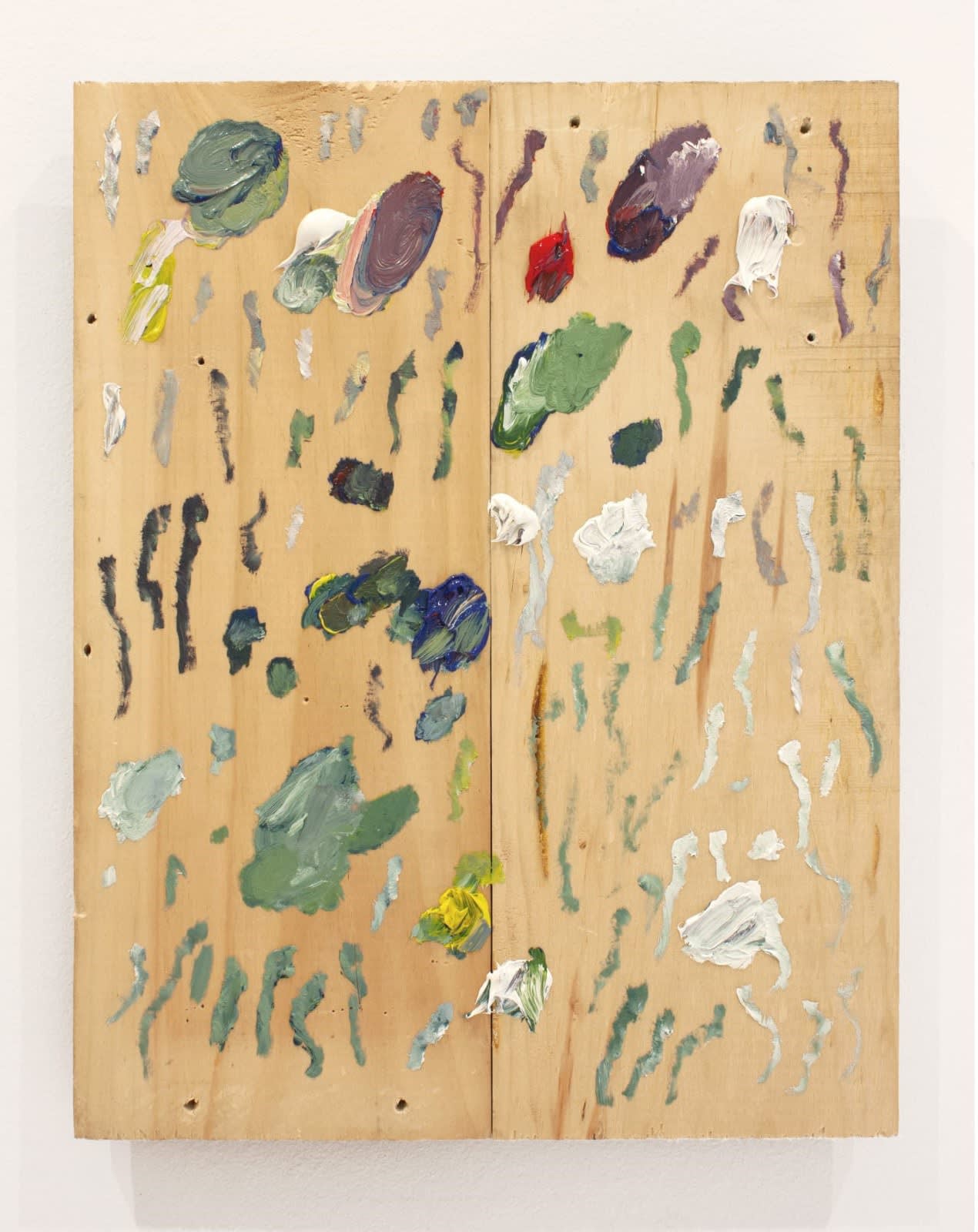

Turning around, I see Mistletoe, which is most closely related to the work I remember Angus making when he was still in London. It joins two pieces of wood, the grain conversing, and I wonder whether it is a point of departure. I want to ask him when this was made, whether it was one of the first in this room. The paint on this bears traces of him working on other pieces in here when the work was still a palette. I can see him trying, mixing. There are invisible connections between the pieces throughout the room and everyone who I point this out to finds this exciting. Constellations work as guide points through the show.

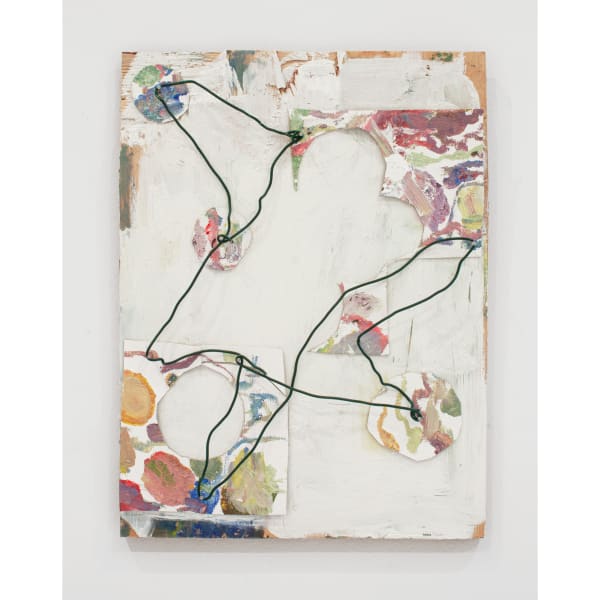

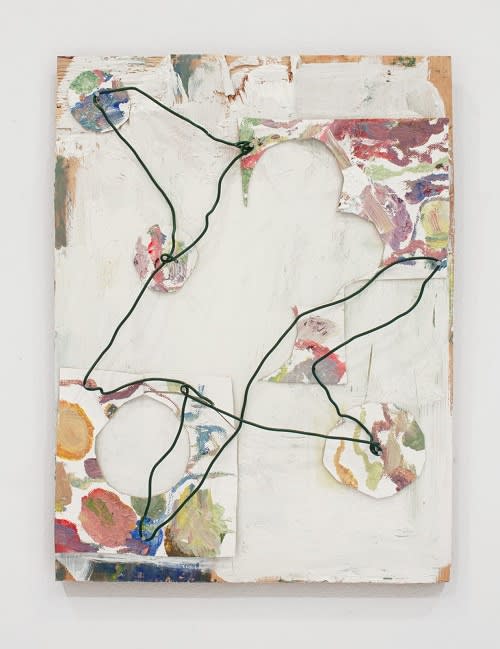

Next to Mistletoe hangs Early Summer Folly, one of three works in the show that contain fragments of a wall. When I meet Angus at Sapling after he had installed the show, he tells me that it was part of a Schrebergarten colony close to where he works in Berlin and that it was old and had been painted many times, layers upon layers. One could easily peel pieces from the damp brickwork. Hearing this, I imagine the sound when the fragments come off the wall. Angus tells me he took them home, mounted them on wood and repaired them with the colours the wall suggested to him.

A Schrebergarten is a little allotment one can rent or buy. They are usually outside small towns, often near carriageways. People go there on the weekends to escape their urban surroundings, to work in the garden, hang out with the family - generations together. Maybe to grow fruit and vegetables. Build a shed.

We didn’t have a Schrebergarten growing up, but one of my oldest friends’ family did and I remember birthday parties there, and that they had a patch to grow vegetables and berries, and that the neighbours had a pond with fish and frogs. They had a tall, green metal frame with a swing, too. Later, as teenagers, we spent every summer weekend there. I remember campfires and love confessions. Away from the watch of adults, this was a space where we would drink our first, grapefruit juice infused beers. Kept cool in buckets of water, the labels came off and were stuck to the beams of the swing, as if it was growing up with us.

On the phone with Angus, I say: this is what Schrebergärten do - they contain memories, both immaterial, but also material ones. This is what he does: walking through the paths between the gardens, talking to people and finding things, collecting stories and materials.

At Sapling, I overhear someone talking about the wire in Six Stars and Stars / Stretching, and that this wire is what unites all the Schrebergärten: It surrounds every allotment as a fence, dividing and securing the space. Wire and wood fences - Jägerzaun - as well as hedges and walls, but also invisible lines between neighbours, mutually respected and strong enough to not need a fence. Walls keep strangers out and others in, just like the one in Berlin, which someone else mentions at Sapling when we talk about your work. When the wall fell in 1989, it had become a surface to be sprayed over and fragments of it started circulating, gaining different value and meaning, becoming part of other objects.

The painted parts of the wall that makes the Schrebergarten-works have also been removed, Angus tells me. But his experience with the gardens is less one of walls, he adds, and more one of exchange and warm welcome. There were encounters with the people tending to the gardens, and there were stories, community and the pride with which they protected and maintained their spaces. I think of the gardens in my hometown, with their perfectly pruned roses, kitschy scenes of gnome figurines and fully equipped sheds, and agree.

I haven’t been to my friend’s garden in a decade now, but he recently sent me some photos of him and a few friends fixing the roof of their shed, all self-taught, taking over the garden from their parents to keep the balance between maintenance and change.

Angus approaches materials others would ignore or discard with respect and curiosity for their history. He finds what’s hidden in plain sight and turns that into the objects surrounding me. They are landscapes referencing the place where they have been found and at the same time a place Angus has taken them to. I remember when we were colleagues, I would sometimes use his computer and find images saved on the desktop - dogs, artefacts, unknown sites. This, too, felt like seeing him walking, thinking, making.

When you take the overground from my hometown into the city you pass a number of Schrebergarten colonies, always located between towns. It’s a scene one would find in any suburban environment in Germany. They are like a hidden world that one wouldn’t enter unless one has their garden there, but Angus does, and his work is the reward for this.

I research Schrebergarten, having never thought about the word itself; it was just something one learns as a child and never questions. Garten is obvious, and I learn that Schreber was a person but ultimately didn’t do more to the garden itself than lending his name posthumously. He was a professor of medicine and head of a sanatorium in Leipzig in the middle of the nineteenth century, meaning he was constantly confronted with the toll industrialisation took on people living in the city. To support people’s health, he encouraged the practice of gymnastics and demanded the city to create green spaces to serve as playgrounds, but never actually spoke of gardening. It was his son in law, a headteacher, who build a playground, named “Schreberplatz,” and another teacher who started a gardening project with the children, that then became little family allotments that are being tended to even today. A story of healing and collaboration.

The idea of healing in Schrebergarten is something that Brine Leat contains, too. The work uses high-quality Dibond as its base - not a material Angus would typically use, Jon said when he came last week - but Angus tells me he found it as a discarded sign, which I understand makes it democratic again. I look at the blues and yellows and the three images: a Gradierturm and a person shovelling salt, as well as an enlarged photograph of two ticks on a flower that makes me uneasy. I ask Angus about the time when he had been bitten by one a year before leaving for Berlin, contracting Lyme disease afterwards. I wonder whether he still has that tick, but we don’t talk about this over the phone, instead, he tells me about his visit to Schönebeck, a spa town in the east of Germany near Berlin, another place I hadn’t heard about but could relate to immediately.

He talks about the local salt production at the Gradierwerk there, a structure made out of a wall-like (walls, again) frame holding bundles of brushwood. Saltwater is poured down, allowing it to evaporate and leaving behind the salty minerals on the brushwood twigs.

Imagine a waterfall, reduced to a trickling sound that is almost inaudible, but creating sprays of water if you get close to the tower. Imagine walking by the sea, licking your lips, tasting salt. I know this because I was in Germany for a few months during the beginning of the pandemic and a friend - the same one that has the garden - took me to a Gradierwerk near where we grew up. Being there felt so refreshing, so healing.

As we talk, I find the town’s crest. It contains a basket with salt. The town’s salt has healing qualities, Angus tells me, and he used this salt in Brine Leat.

My hometown did salt too, I say, but they weren’t profitable enough beyond the industrial revolution. We have springs that are said to have healing qualities, which I have tried as a child and didn’t like, but my friend’s grandmother would swear by it, filling plastic bottles with the briny, warm liquid that I can see being used for making salt.

Our conversation arrives at the concept of Kur, etymologically related to ‘cure’ referring to prescribed spa holidays paid for by insurance. This has changed now, but needless to say, Kur was very popular with the elderly, amongst them my grandparents who I remember going off to Kur when I was a child. The parks in spa towns like these would often be called Kurpark, and I imagine the past when people would flock to those towns, strolling in the parks, healing. My hometown, also a former spa town, has two of them in a valley. The springs are inside. I think they must be emitting steam, now that it is getting colder.

Recently, Angus told me that he was moving from the place where the pieces in the show were made. The new flat is on a main road and I am sure that he can hear Berlin there. As I finish writing this, I am back in central London, the traffic rushing outside.